Versailles: town

Designers propose; common humanity disposes, thank God. Versailles town is the real proof of the success of the French Revolution, and a key to the astonishing resilience of Parisians. Louis-le-Grand in his witless way carved up the town in front of the chateau with three huge avenues. Also, vain as well as witless, he discouraged conspicuous decoration in his courtiers’ buildings in case it invited comparison. Hence an austere town grew up; on a formal plan, with a few formal gestures interrupted by boulevards as brutally as Haussmann’s Paris. And it has turned out to be a wonderful framework for ordinary French life: the restraint of the buildings sets off the urbanity of the people who use them: the formal gestures become animate and comprehensible. Even the avenues cannot break this vitality.

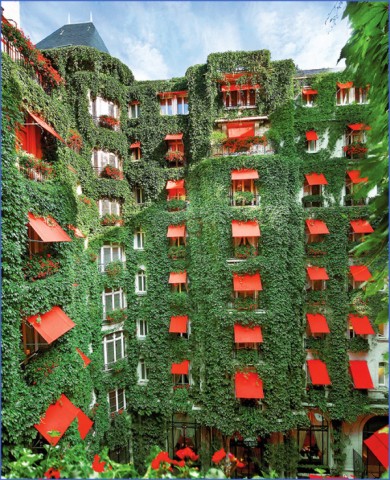

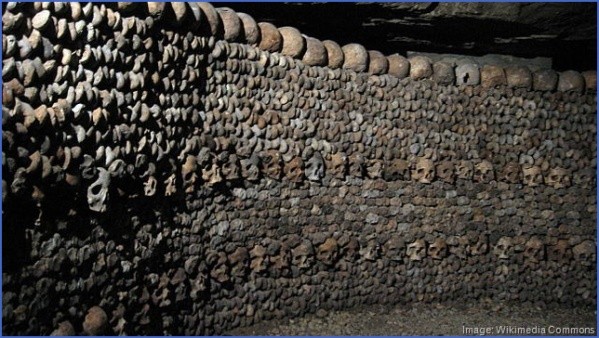

What To Do In Paris France Photo Gallery

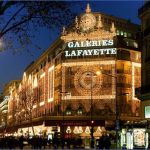

Best Location To Stay In Paris

Versailles: Place du Marche-Notre-Dame

Market: Le Poittevin, 1841

After repeated visits to Versailles, I reckon that this is the best formal effect in either town or chateau. The market, a tube of buildings forming an octagon, is inscribed in a square which is also a main crossroads. The central space becomes an open market; the diagonal corners of the octagon are pierced to reveal what goes on behind in the corners of the square. All four corners are also pierced: one to a courtyard, two to public alleys, one to the Hotel du Cheval Rouge, well known to English visitors, with a delightful pedimented entrance which is ready-made for open-air theatre. To walk around the edges of the square, experiencing in turn street, triangular cut-off space, street, main road traffic, is exhilarating, vital and human – all the qualities that are missing in that great lummox at the top of the hill. And the balance of formal and unplanned is also exactly that of the French themselves in any of the cafes around this square: the grand ‘messieurs, mesdames’ as they come in the door, the grunts and expressive silences afterwards.

Versailles: cathedral

Hardouin-Mansart de Sagonne, 1743-54

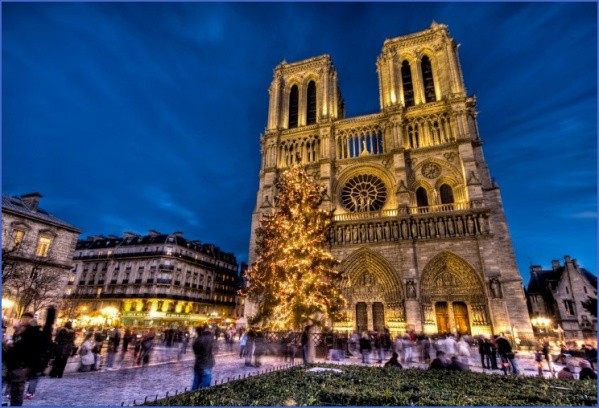

This has always been an unwanted ugly duckling. Michelin can only raise ‘cette ceuvre un peu froide ’ and an absence of stars. It seems hard luck on an unfashionable but noble building. Mansart de Sagonne had no new ideas, but he endowed the old ones with gruff meaning, tramping on square-cut into the rain like an indomitable old man. Just what he did can be seen by comparison with Notre-Dame on the other side of Versailles, done by that more famous Mansart who was his grandfather: almost the same design, but no feeling at all. Versailles Cathedral is full of feeling, well buttoned-up, and also has a sense of its own awkwardness – an awareness which is in the end worth all the polish in the world. It is a spirit which fits the sober quietness of Versailles town very well, and the two squat towers of the west front deploy on either side of the scrolls to face a little square which does more than impress: it involves. Inside, it is obligatory to sit down and let the intractable honesty sink in. Bare and introspective, the most Protestant of eighteenth-century Catholic cathedrals; the space serves as a sounding-board for thought, transformed by the double line of glass chandeliers with their dusty velvet tops. The bishop’s seat, opposite the pulpit, is as noble a piece of impersonal sculpture as the golden huissiefs sign, but this is no place to look at single objects. The tone is set by the vast organ-case on its vast three-dimensional curved arch, filling the west end: an uncompanionable, lonely voyage. Rameau who was academic, abrupt, gloomy and passionate would match the building exactly.

Versailles: Musee Lambinet

A jolly, crowded eighteenth-century hotel with all the atmosphere that is lacking in the Petit Trianon. The entrance from the boulevard de la Reine is a delight: a formal gravelled courtyard with the ornate elevation at the end. There is nothing special in the design of the rooms, but the objects give the impression that the eighteenth-century owners have merely gone on a protracted holiday. It is primarily a Houdon museum (he was born at Versailles in 1741) and his humane, perceptive personality is everywhere, most notably in a tiny full-length terracotta figure of Voltaire. But there are many other things as well, including some crude but highly effective souvenirs of Marat. It is the kind of place where odd objects are always turning up – and you can go where you like, unnudged, even up to the attics.

Maybe You Like Them Too

- Top 10 Islands You Can Buy

- Top 10 Underrated Asian Cities 2023

- Top 10 Reasons Upsizing Will Be a Huge Travel Trend

- Top 10 Scuba Diving Destinations

- World’s 10 Best Places To Visit