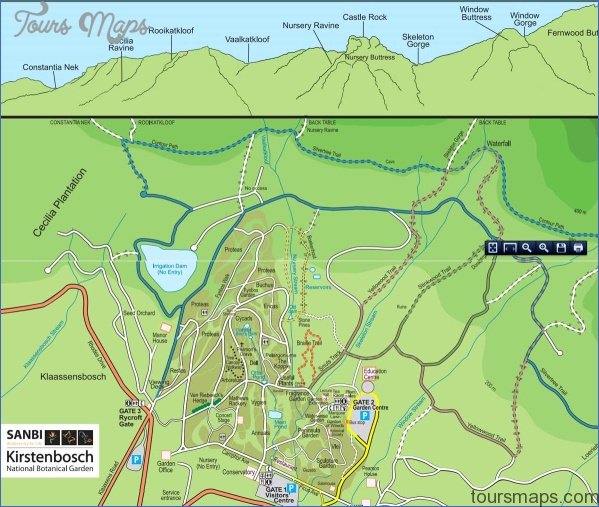

Forest streams burst through the undergrowth after an autumnal downpour. A necklace of isolated patches of moist, Afrotemperate Forests, starting in Ethiopia, stretches southwards through East Africa, Malawi, Zimbabwe, Mozambique and the KwaZulu-Natal escarpment, ending in the ravines of Kirstenbosch. Here remnant natural forests in the Nursery Ravine and Skeleton Gorge protect some of the southernmost outliers of the rich Afrotemperate Forest flora. The forests on Ruwenzori, Kilimanjaro and Mount Kenya, and many of the mountains of the eastern escarpment, carry a similar but much richer forest flora to these relict patches in Kirstenbosch, which remain as reminders of an earlier, cooler and moister climate. Only 33 tree species occur naturally in the Kirstenbosch forests, but several of them – Cape Beech Rapanea melanophloeos, African Holly Ilex mitis and White Pear Apodytes dimidiata – are common to forests stretching from the equator to the Cape Peninsula. Although Kirstenbosch entered recorded history as ‘Leendertsbos’, implying a forested estate, and despite early efforts to protect these forests, little remained by the end of the 18th century of the fine trees that once provided a dense canopy and the special microclimate needed to sustain the forest fauna and flora. Invasive trees, shrubs and climbers filled the gaps left by the woodcutters. Following a 50-year programme to remove invasive alien plants from the forests, initiated by Jack Marais (Curator 1959-1979), recovery has been impressive. Leading the recovery were pioneer species such as Keurboom Virgilia oroboides, Tree Fuchsia Halleria lucida, Turkey Berry Canthium inerme, Wild Pear Kiggelaria africana and Cape Myrtle Myrsine africana. Good specimens of Ironwood Olinia ventosa, Wild Olive Olea capensis, Bastard Saffronwood Cassine peragua, Assegai Curtisia dentata, Bladdernut Diospyros whyteana and Rooiels Cunonia capensis now clothe the cool, moist ravines above the main Garden. New plantings of the most sought-after cabinet woods, such as Real Yellowwood Podocarpus latifolius and Black Stinkwood Ocotea bullata, have yet to replace the mighty trees felled in the 18th century.

Bulbinella latifolia var. doleritica is one of the 309 species of geophyte found on the Bokkeveld Plateau, making the Nieuwoudtville region the ‘Bulb Capital of the World’.

Kirstenbosch National Botanical Garden Time Zone Map Photo Gallery

Most travellers in the northwestern Cape pass through the sleepy little village of Nieuwoudtville without stopping. But the area is now popularly referred to as the ‘Bulb Capital of the World’: the epicentre of South Africa’s unequalled richness in bulb species, with no fewer than 2 200 species occurring in the region. By comparison, California has 250 species, Chile 250, Australia 750, and the whole Mediterranean Basin some 1 335 species.

In 2007, the Hantam National Botanical Garden was established at Nieuwoudtville, the ninth NBG in the national network (see page 230). Before this, horticulturists at Kirstenbosch were faced with the challenge of ex situ conservation of the many rare and endangered species of the Cape’s stunningly beautiful bulbs. A few genera (Agapanthus, Dietes, Eucomis, Chasmanthe, Clivia, Gloriosa and Watsonia) are able to endure the heavy winter rainfall in Kirstenbosch if planted in well-drained soils – and are fortunately not attacked by the Garden’s healthy populations of molerats and porcupines. But most bulbs constitute the preferred diet of these Garden inhabitants, and cannot be planted out in the beds. Mathews was to learn the hard way: in a single night in 1916 he had 100 metres of newly planted bulb beds destroyed by a single pair of visiting porcupines.

Kirstenbosch bulb expert Graham Duncan has built a scientific collection of over 900 bulb species, mainly spring flowering. Of these, 221 are threatened in the wild. To protect them from the predations of molerats and porcupines, most are grown in pots in the Garden’s large Millennium Glasshouses, where the scientific and ex situ conservation collections are held. As they come into flower, the bulbs are displayed in the Conservatory, a ‘must-see’ in spring and autumn. Because they are grown in bulk in the greenhouse, potted bulbs can also be displayed in the Garden, with the pots being ‘plunged’ in autumn and lifted after flowering in late spring, and returned to the nursery for the summer dormant period.

The Hantam NBG area is not only the Bulb Capital of the World; it also lies adjacent to the heart of another botanical spectacle – Namaqualand. Flower tourism in South Africa is strongly promoted by scenes of the spring flowers of Namaqualand. Fields of daisies stretch from horizon to distant horizon, with palettes of white, yellow, orange and mauve, and scattered splashes of red and blue. Kirstenbosch creates its own spring displays by the careful selection of species adapted to its rather moist, and less sunny, climate. An explosion of colour is presented in September – felicia, euryops, senecio, cotula, dimorphotheca, osteospermum, ursinia, arctotis, gazania, arctotheca and many more.

While Pearson is rightly honoured for his vision and determination to establish Kirstenbosch, it was Joseph Mathews, more than anyone else, who gave this modern Eden shape and colour. It is fitting to conclude this chapter with a quote from his farewell speech:

Maybe You Like Them Too

- Top 10 Islands You Can Buy

- Top 10 Underrated Asian Cities 2023

- Top 10 Reasons Upsizing Will Be a Huge Travel Trend

- Top 10 Scuba Diving Destinations

- World’s 10 Best Places To Visit