ODO OF METZ

Commissioned by Charlemagne, the king of the Franks (later Holy Roman Emperor), as part of his great palace complex at Aachen (also known as Aix-la-Chapelle), the imposing Palatine Chapel became the emperor’s final resting place and the site of successive royal coronations. Charlemagne’s palace has not survived, but the chapel remains (albeit with extensions from the 14th and 15th centuries) as one of the best examples of European architecture from the so-called “Dark Ages. Charlemagne and his architect-probably Odo of Metz, who is mentioned in an early inscription chose an unusual plan for the chapel, which has 16 sides converging on an octagonal dome. This dome-centered plan was influenced by Byzantine churches, such as Hagia Sophia (see pp.32-37) in Constantinople (Istanbul) and San Vitale in Ravenna, Italy. By imitating the building projects of the Christian rulers of the Byzantine (eastern Roman) Empire, Charlemagne was reinforcing his own claim to the title of Emperor: he was crowned by the pope on Christmas Day in the year 800.

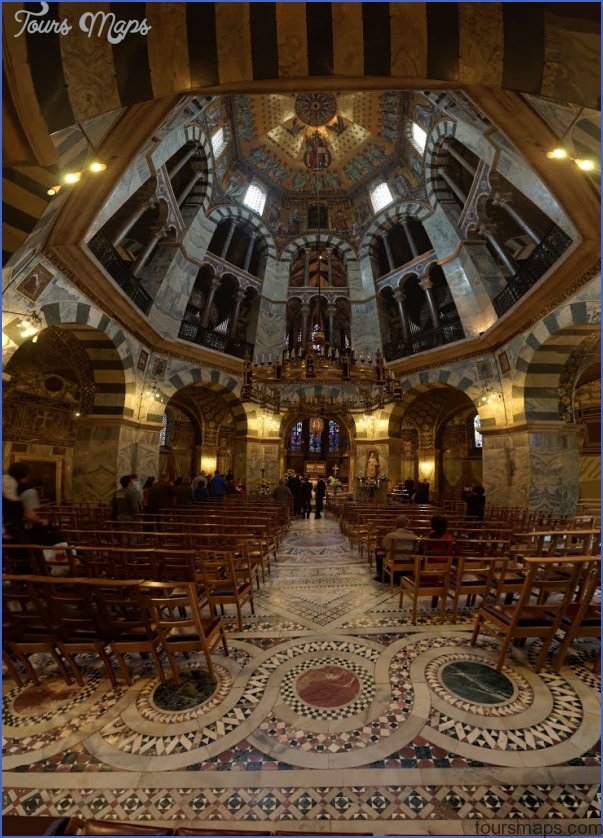

Although the chapel draws on the influence of the great Byzantine churches, it is not a large building-the dome measures just 47.5ft (14.5m) across. The architect used a simplified version of the Byzantine style, which also draws on earlier Roman models. Barrel and cross-vaults roof the 16-sided ambulatory, and the dome in the center also has a cross-vault. The decoration of these spaces displays a rich but sober quality that complements this simplicity. The polychrome masonry of the arches and the colored marble lining the walls enhance the effect, as do mosaics in the vaults and sumptuous bronzework and gold fittings. The richness of the decorations, which glowed in the light from the windows and candles, created a glittering, magical interior.

CHARLEMAGNE c. 742-814

Charlemagne was the ruler of the Franks, a Germanic people originally from the Rhineland, who, from the 5th to the 8th centuries, expanded their territory to occupy much of what is now France, Germany, and the Netherlands. He defended his territory, against attack from eastern peoples, such as the Saxons, whom he defeated in battle, and annexed large territories in northern Italy to create the greatest European empire since the Romans. Conquests in Italy then made him the protector of the pope, who crowned him emperor. Although the empire did not survive for long after Charlemagne’s death, it was hugely influential: in the following centuries many German rulers took the title of Holy Roman Emperor and aspired to wield pan-European power.

Visual tour

DOME The octagonal form of the dome rises above the 16-sided ambulatory that surrounds it. These outer walls of the chapel are very plain. On the lower levels are simple round-topped windows and pilasters (slight vertical protrusions) at the corners. The gables above are more ornate, but still follow the same style, with rows of blind, round-topped arches and very small window openings. This exterior simplicity is typical of early Christian architecture, which covered highly ornate interiors in very plain outside walls: builders considered the exterior worldly and kept it distinct from the sacred space within.

DOME INTERIOR A series of eight marble-clad piers hold up the polychrome arches that support the weight of the dome. This space is very high, and the architect based its proportions and dimensions on the description of the New Jerusalem in the Book of Revelation. The distance from the floor to the top of the dome is 118ft (36m).

PULPIT The pulpit was a gift to the chapel from Emperor Henry II, who was crowned here in 1002. Henry’s entitlement to the imperial crown was at first disputed, and he probably donated the pulpit as a gesture of thanksgiving for the support that enabled him to be appointed emperor.

It is made of gilded copper and studded with precious items including ivory reliefs, crystals, and semi-precious stones.

1 VAULTING The ambulatory surrounding the central space is roofed with simple cross-vaults, each with four roughly triangular compartments covered in decorative mosaics. Natural light from the round-topped windows originally made the golden tesserae (cubes) of these mosaics glitter brightly, but this effect was reduced by the addition of smaller chapels that cut down the amount of natural light.

ON CONSTRUCTION

By the 14th century the chapel had the status of a cathedral, and frequently there was not enough space for the crowds who flocked to Charlemagne’s shrine or to attend imperial coronations. To increase capacity, the cathedral commissioned a large new choir (a long space with an apse, or a semicircular end) in the Gothic style. Stained-glass windows line the sides and the apse, and the entire space is topped with a pointed stone vault. The windows are 89ft (27m) tall and reach almost to the stone vault. The jewel-like setting they create makes a fitting home for the gilded shrine of the emperor, which medieval pilgrims visited in huge numbers.

1 Stained glass

The glass in the choir windows was installed after the building suffered bomb damage during World War II, but the effect is similar to the original.

1 SHRINE The shrine that contains the remains of Charlemagne’s body has been dated to the late 12th century. It consists of an oak chest just over 6.5ft (2m) long, covered with silver and gilded decorations, including golden statues of the Virgin Mary, Charlemagne, and many successive emperors.

2 COLUMNS AND CAPITALS

The semicircular arches are divided by slender vertical columns topped with crisply carved Corinthian capitals in the classical style. These columns are not significant structurally but serve an important symbolic purpose. Some of them are made of porphyry, and Charlemagne had them brought to his chapel from Ravenna and Rome. In the ancient world porphyry was used only for imperial buildings, and, by employing it, Charlemagne claimed a link with the rulers of the Roman empire.

IN CONTEXT

The model for the Palatine Chapel and other round and polygonal churches is thought to be San Vitale, Ravenna, which was begun in 526. An octagonal building crowned by a dome supported on arches, it is richly adorned with mosaics. Ravenna, the capital of the western Roman empire after the fall of Rome, was later a focal point of the Byzantine empire. It was natural that the builders of the Palatine Chapel should look to San Vitale for inspiration.

1 San Vitale, Ravenna, Italy

Although details such as the round columns and capitals differ, San Vitale has a similar style and plan to Charlemagne’s chapel.

CHAPEL AACHEN, GERMANY Photo Gallery

Maybe You Like Them Too

- The Best Cities To Visit in The World

- World’s 10 Best Places To Visit

- Coolest Countries in the World to Visit

- Travel to Santorini, Greece

- Map of Barbados – Holiday in Barbados