ENESCU MUSEUM

The Romanians take enormous pride in George Enescu: he was a great violinist and teacher, a composer of international stature and a man who deeply loved his country. Streets, competitions and festi-

Enescu’s birthplace at Liveni and watercolours); in the centre of the larger room is a bust of Enescu and on the walls are display boards telling his life story. Last is however best: in the small back room are five manuscripts (dating, of course, from after the Liveni period) representing some of his earliest efforts at composition.

Enescu was quickly recognized as a musical prodigy and in 1888 his family moved to Vienna so that he could study at the Konservatorium. A plaque with a portrait relief marks the house at Frankenberggasse 6 in the fourth district where they lodged. In January 1895 the 13-year-old was taken to Paris where he lived in Montmartre, at 10 rue Chaptal, and studied composition at the Conservatoire under Massenet and Faure. He played his violin concerto at the Salle Pleyel in 1896 and made his conducting debut in Bucharest the next year. He was deeply involved in chamber music, both in Paris and Bucharest. He came to the attention of Romania’s music-loving Queen Elisabeth (herself a poet, under the pseudonym ‘Carmen Sylva’), consort of King Carol I; she was a generous patron. At her summer retreat, Peles Castle at Sinaia (at the foot of the Bucegi Mountains between Bucharest and Brasov), she held chamber music evenings in 1905 in which Enescu played; on another visit, in 1910, he met his future wife, Maria Rosetti, Princess Cantacuzino.

When in 1909 his mother died, his parents had for some time been living apart. In 1910 his father, Costache, bought a spacious, wood-trimmed stone house, with a narrow porch along the front, in Dorohoi, a larger town, near Liveni, some 40 km north of Suceava; on his death in December 1919 it became Enescu’s property and in 1957 it became a memorial museum, although he never actually lived there. In a small room at the back, his father’s carriage may be seen. The five main rooms contain displays of Enescu’s own furniture, his travelling bags and concert clothing (his Legion d’honneur pinned to the lapel), his death mask and a cast of his hands; a necklace and ring he gave his mother and a watercolour of the family house in Mihaileni where his mother died and which he also inherited; there are posters for benefit concerts he gave in Dorohoi for a local hospital (1916) and theatre (1921), and statues given to him when he was made an honorary citizen and on the premiere of his opera Oedipe (1936). There are also editions of his music and programmes of his recitals as well as important portraits, a wealth of photographs recording his life, facsimiles of important documents such as his will, and a collection of commemorative stamps.

ENESCU MUSEUM Photo Gallery

In 1924 Enescu authorized building to begin on a large, three-storey house in Sinaia designed for him by the architect Radu Dudescu. Known as ‘Vila Luminis’ (The Glade), it stands above the railway in a forest of spruce trees with a view of the mountains; Maria Rosetti Cantacuzino financed it. Enescu and the now widowed princess (they married only in December 1939) spent some two months there each summer until 1946, and this is where he is said to have composed much of Oedipe. Yehudi Menuhin, who had been studying with him in Paris (Enescu lived at that time at 26 rue de Clichy) since February 1927, went to Sinaia for lessons in 1928.

Although Enescu relinquished ownership of Vila Luminis and the properties he had inherited from his parents in 1946 to the Romanian State, in exchange for a passport to the West, a museum, with a

Vila Lumini§, Sinaia ground-floor recital room seating 60, opened there in 1995, 40 years after his death. The first-floor rooms are furnished much as they were in Enescu’s time. Particularly evocative is the music room, decorated in yellow velvet, with its corner tower and circular staircase, his Ibach grand piano, furniture, north Moldavian wool-embroidered drapes and 19th-century Romanian and Ukrainian icons; in an alcove are ornately carved wooden chairs with tooled leather backs and seats. The composer’s bedroom is decorated entirely in traditional Romanian style, with woven carpets on the walls as well as the floor, a needlepoint bedspread on the small single bed, folk ceramics, a brass lamp and several 18th-century icons. Upstairs are four rooms, three of which are still used for chamber music rehearsals. One was where Menuhin practised during his two months in Sinaia; across the hall are two larger rooms with display cases containing photographs and documents relating in particular to Enescu’s friendship with Carmen Sylva (next to the Peles Castle, itself now a museum, is the Palace Hotel, where there is a memorial to him).

Enescu and the princess often visited her family estate at Tescani, a village 35 km from Bacau, just one and a half kilometres south of the 2G road to Moinefti. The Rosetti Tescanus were a noble family who had owned property in the area since the 16th century. The house, built in 1880, serves today not only as a museum but also as an arts centre, with facilities for concerts, conferences and residential courses. Here on 27 April 1931 Enescu finished Oedipe, which he dedicated to his beloved ‘Marouka’, and it was there that he wanted to be buried (a statue of him mounted on an empty tomb, by Ion Jalea, a short walk into the surrounding woods from the house, symbolizes his unfulfilled wish to return to his homeland; there is a lifesize copy of the statue at the museum in Dorohoi).

The museum at Tescani-Bacau commemorates the Rosetti family and another of their distinguished musical relatives, the composer Mihail Jora (see Jora), as well as Enescu. The foyer is dominated by the large family tree and family photographs. To one side is the Camera Rosetti, furnished with family heirlooms and lined with portraits and birth certificates. A large room at the front is devoted to Enescu, containing many original documents (including an acrostic he devised and dedicated to the Bucharest Symphony Orchestra in 1946), signed editions, programmes and reviews, recordings and a few of his personal possessions, including his glasses, a calling card, one of his diaries (which doubled for notating sums and musical ideas) and a medal he received on his 65th birthday. There are also telling caricatures, telegrams from Lalo and Dinu Lipatti, and a copy of a Siciliana (op.1 no.1) by Constantin Nottara dedicated to Enescu in 1913. The wall panels do more than narrate his life; they focus on his relationship to his younger contemporaries (especially Lipatti, Serge Blanc and Menuhin) and to other musicians who came to Tescani. The Oedip Room, the largest in the house, is reserved for concerts and large gatherings. There are two boudoir grand pianos and a bust by R.P. Hette of Enescu as a Roman, two cases devoted to Oedipe and posters of different productions of the opera on the walls. There is a deeply moving large oil portrait by G. Stoenescu of Enescu in his study, old and ill, a rug over his knees. On the far side of the Oedip Room are two memorial rooms, one to Enescu, furnished with his carved desk, an Erard grand piano and a phonograph (Gramofon Master’s Voice), the other to Jora. During their final years (1944-6) at Bucharest, before Enescu and his wife ceded their Romanian properties to the State and left for the West, they occupied a building reached by a dramatically curving, oversized staircase in the grounds of the Cantacuzino Palace, which the princess had also inherited from her first husband’s family and in 1955-6 ceded to the State on condition that it be preserved as a memorial. Enescu rejected the grandness of the palace, though he and his wife entertained there, and opted instead for the simpler environment of the former palace administrative building, just behind it. Restored, the five rooms are furnished much as they were when the Enescus lived there. The central hall is lined with framed pencil studies of Enescu and the laurel wreath he won for Oedipe. On the right is his music salon, furnished with his Pleyel piano, a desk, music stand and metronome and portraits, with a tiled stove, woven carpets and velvet curtains. At the back is the bathroom with its original fixtures (including a stove for the bath) and on the left of the hall are two further rooms, the elegant Camera Madame and the composer’s bedroom and study: as at Sinaia his bed is covered with a needlepoint spread and there are icons on the walls, with a desk and leather armchair, a crucifix and a death mask of Beethoven, a violin and travelling cases on one side of the small room. This Casa Memoriala can be visited as part of the George Enescu Museum in the palace.

After six months in the USA, the Enescus settled in France, taking a villa, Les Cytises, at Bellevue (Seine-et-Oise), returning to New York in 1950 for a farewell performance of the Bach Double Concerto with Menuhin and the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra under fellow countryman Ionel Perlea at Carnegie Hall. On the night of 13/14 July 1954 Enescu suffered a paralytic stroke at home in Paris. By this time impoverished, the Enescus moved, with Menuhin’s help, from their old flat in the rue de Clichy to the quieter Hotel Atala, at 10 rue de Chateaubriand, near Etoile, where he continued in spite of his infirmities to compose. George Enescu died on the night of 3/4 May 1955, attended by no less than the Queen of Belgium, and was buried at the Pere Lachaise cemetery.

In 1955 the Cantacuzino palace became the seat of the Union of Romanian Composers, which was later joined downstairs by the offices of the music and music journal publishers. The

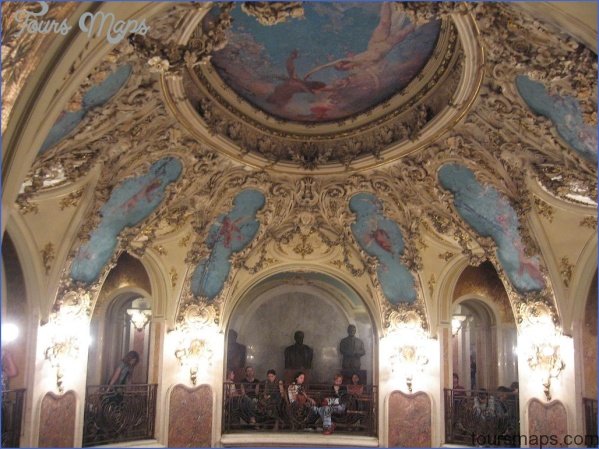

The Casa Memoriala at the Cantacuzino Palace, Bucharest formal reception rooms on the raised ground floor, decorated in an eclectic Art Nouveau style, have high ceilings with exquisitely painted murals and gilded cornices. The large, domed central room, with curved balcony, all mirrors, marble and red velvet, seats 300-400 and is acoustically very fine. To the left is a splendid barrel-vaulted dining-room decorated with stained glass, Gobelins tapestries and huge carved wood sideboards; to the right is an auxiliary music room used for special events, including receptions, recitals and exhibitions. Three rooms at the front of the building, on the right, display the museum’s unrivalled George Enescu Collection.

The museum opened in 1958, but closed between 1977 and 1992, during the Ceaucescu regime; it re-opened after refurbishment only in 1995. This, the Rights were not granted to include these illustrations in electronic media. Please refer to print publication The Cantacuzino Palace, Bucharest central George Enescu museum, curates most of his manuscripts, letters, citations and other unique documents, editions of his music, concert programmes and recordings, portraits, original photographs and sculpture, his Guarneri violin and his Steinway grand piano. The rooms are chronologically organized. First, 1881-1900: his Vienna and Paris conservatory diplomas, early childhood manuscripts and a letter from his mother are displayed, and there is a case devoted to his Poeme Roumain of 1887-8. The room for 1900-20 shows original photographs of Queen Elisabeth’s Sinaia salon and a music stand, on which is displayed Enescu’s manuscript cadenza – written in pencil and ink – for Paganini’s First Concerto. Lastly, 1920-55: this exhibits manuscripts of some of his best-known works, his desk from his Paris flat at 26 rue de Clichy (on which a facsimile of Oedipe is displayed), his concert and academic attire, and an original death mask and casts of his cruelly gnarled hands.

Maybe You Like Them Too

- Top 10 Islands You Can Buy

- Top 10 Underrated Asian Cities 2023

- Top 10 Reasons Upsizing Will Be a Huge Travel Trend

- Top 10 Scuba Diving Destinations

- World’s 10 Best Places To Visit