Nuclear Bombs and the Reset Button

While enjoying my new perspective and waiting for a shipment of propane to arrive, I put some miles on my bike riding between the scattered villages named for the original World War II stations. Men wrap their lower half in bright cloth lavalavas, and women wear handmade tibuta shirts and skirts. The stilted kiakias (homes) are built mostly from parts of coconut palms. Communication is a challenge, but the I-Kiribati are both welcoming and creative. The employees at the town hall even make me a makeshift desk one afternoon so I can use their Internet connection.

Although the peoples of Kiribati speak Gilbertese and differ in culture from those I’d encountered in French Polynesia, they share some grievous historical similarities. Alongside colonization (mostly by the British in Kiribati), evangelical missionaries did extensive work in the Pacific Islands starting in the 1800s. Seven churches line the main road within the span of five miles, serving a population of about 2,000. The missionaries forced Western beliefs and customs upon the indigenous populations and forbade singing and dancing for a long, dark period. This interrupted the passage of the native peoples’ oral history. Their relationship to nature changed too: Reverent and long-standing resource management practices, like fishing limits, gradually disappeared. They now appear stuck between the two culturally conflicting worlds, and most families and villages are divided by the small discrepancies in the various forms of Christianity.

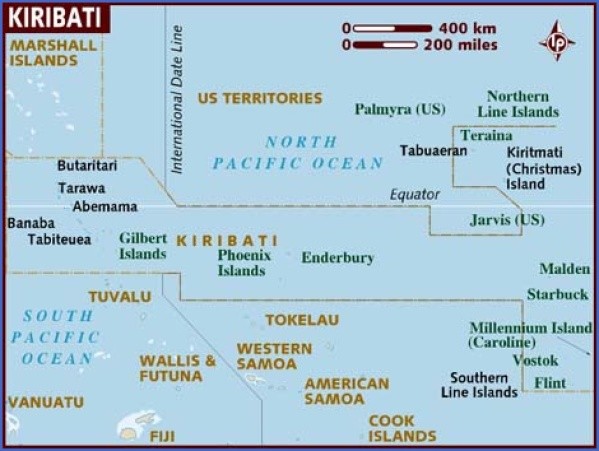

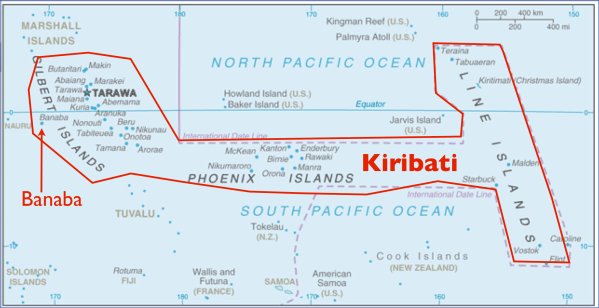

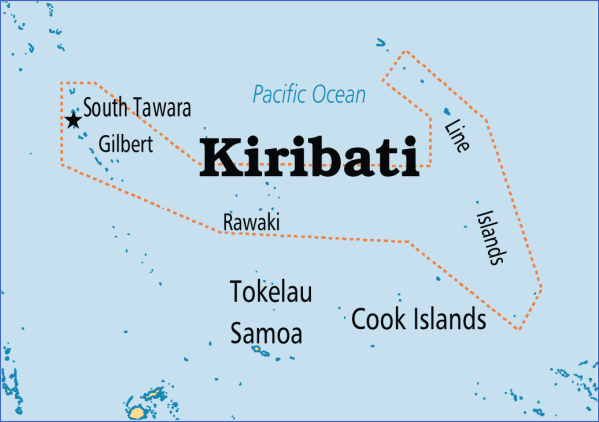

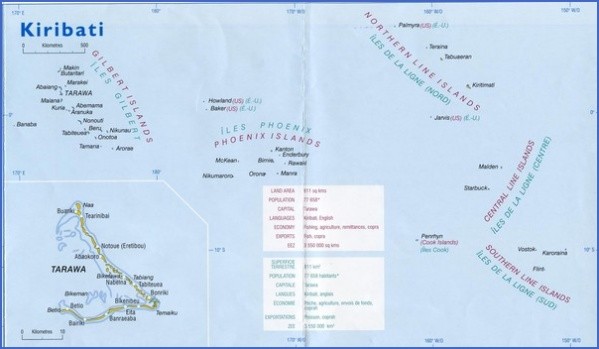

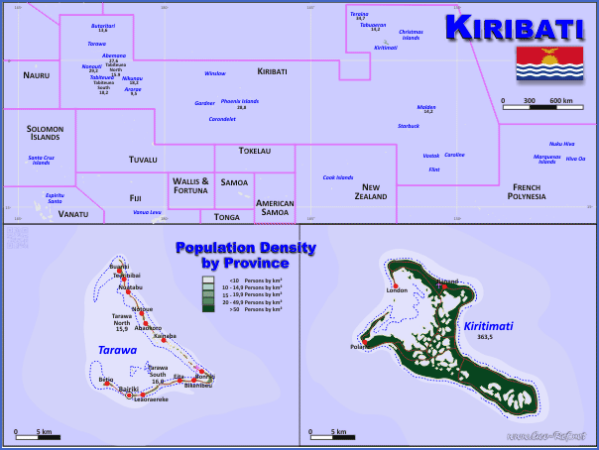

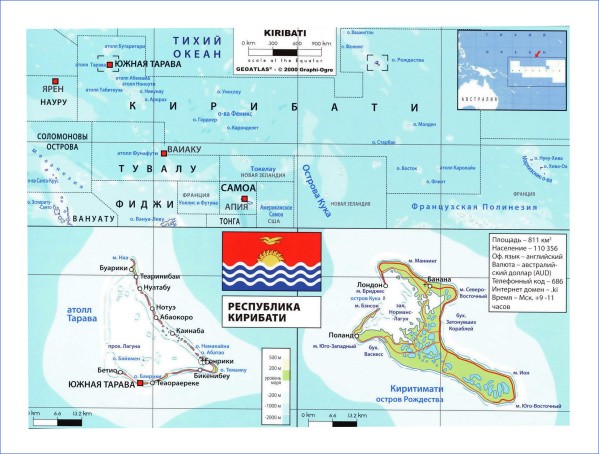

Kiribati Map Photo Gallery

And although the nuclear testing here was much less extensive than the horrors the French inflicted on the Polynesian islands exploding around 180 nuclear bombs in the Tuamotu Archipelago between 1966 and 1996 both the United Kingdom and the United States unleashed nuclear weapons on this island, Kiritimati, in the late fifties and early sixties. It was also used as a strategic base for the Allies during World War II.

Nuclear fallout from the uncontained explosions spread across the Pacific, and continues to be linked to health problems. I was spooked by the green clouds that linger daily above the island, thinking they had something to do with radiation residuals, but Henry quickly assured me that they are caused by a reflection off the turquoise color of the atoll’s enormous, shallow lagoon. “We can’t see the leftover radiation,” he said, “but it’s here.” A UK official is currently here managing ongoing nuclear “cleanup,” but after seeing him toss plastic trash right out his car window, I lost faith in his efforts.

One sunny afternoon after filling my water jugs ashore, I trudge back toward Swell, using my bike as a dolly to push the ten-gallon load back toward the pier. I hear a cacophony of sounds coming from below a low, broad-leafed tree and swerve right to find a small group of kids crowded into the shade, all heartily jamming on instruments made from trash.

A boy of about ten is drumming on an old, tin powdered-milk container with a broken fork and a small stick. Another plucks a string bass made from a plastic jug, a long stick, and fishing line. A tall skinny girl, maybe eleven, drags a small plastic soda bottle across an old piece of corrugated aluminum roofing. A smaller girl uses an empty beer can filled with pebbles as a shaker. The last member of the ragtag band, a tiny girl who can’t be more than four, is sending bold huffs of air through an orange trombone-shaped flower, making it toot wildly. I clap madly when they finish. The beer can is passed to me as they start in again. Like everywhere I’ve sailed, children don’t care about language differences or skin color; they’re always excited to make friends.

All of the I-Matangs pitch in to help Chris get through his implausible hull repair. He manages to get the boat hoisted out of the water and delivered to a grove nearby. My contribution is mostly in the realm of moral support and hydration, arriving with some encouraging words in the afternoon, and climbing the surrounding coconut trees for “atoll Gatorade,” as he calls it. From up in the tree I watch I-Kiribati men sing merrily as they collect sap from the flowering shoots of coconut palms; they’ll ferment it and turn it into toddy, the local alcoholic beverage.

Gaspar continues to make an effort to rekindle our romance, and although it’s flattering, I resist. Until one evening after a little party at Henry’s bar, I see the silhouette of Gaspar’s hair under a tree beside the road. Feeling confident with my new knowledge, I stop and sit down next to him without saying a word. I don’t move away when he puts his arm around me. We lean back into the sand together, and stare up at the stars. My new outlook makes me think being closer with him again will be okay. It could be part of practicing my virtues and learning to control my emotions.

“You know, Lissy, maybe I understand you mejor ahora (better now). Maybe we can at least be amiguetes (friends),” he offers.

“Maybe,” I tease, appreciating his effort and openness. We ride double on my bike back toward the anchorage, him pedaling and me on the handlebars.

“Lissy!” I hear outside Swell the next morning. “Quieres nadar conmigo?” (Want to swim with me?) I don my fins and we swim off to explore the nearby coast. Although he’s awkward in the surf, he has a dancer’s grace underwater calm and confident as he kicks down to the seafloor to point out an octopus or conch. We marvel at multicolored sponges, gaze at swirling packs of baitfish, and dodge wily barracudas. A fart slips out when I’m fifteen feet down and the bubbles float up toward the surface; Gaspar’s mask explodes with laughter. On the next dive down, he reaches out to me and we kick on together, hand in hand.

The morning swim turns into pancakes. Pancakes turn into a siesta. The siesta into sweet love but this time with the notion that nothing is forever. We don’t need to own each other, nor do we owe each other anything besides honesty. With fewer expectations, we start over.

Maybe You Like Them Too

- Top 10 Islands You Can Buy

- Top 10 Underrated Asian Cities 2023

- Top 10 Reasons Upsizing Will Be a Huge Travel Trend

- Top 10 Scuba Diving Destinations

- World’s 10 Best Places To Visit