Versailles: chateau

This is very likely to be a disappointment to an English visitor. It is far too long in one sense, far too short in another: too long in sheer size, both building and gardens, too short in expressiveness and individuality. Vanbrugh had done the same thing at Blenheim with ten times more force. This is not an insular point of view: the Neapolitan from Caserta, the Dane who knows Amalienborg, the German from any of a dozen electoral palace-towns must feel the same. The effect which inspired all the others is in itself a let-down. You can surprise it: the courtyard in misty morning sunshine, or the way that the facade plays hide and seek up the main axis of the gardens, shrinking from three full storeys to the gesticulating top balustrade and expanding again: but these could have been produced by any design of these dimensions. The basic trouble is that to match the scale of either approach or gardens the building itself has to have gigantic power. Ledoux might have done it; Jules Hardouin-Mansart could not, and a sophisticated dialogue is no substitute for genius, especially when stretched to this length. The three-storey core is a cosy enclave from the entrance side and a colossal bore from the gardens; Louis XV realized this and commissioned the younger Gabriel to turn it into a monumental composition, but time and money ran out. Even so, his pedimented fragments, now inscribed ‘A TOUTES LES GLOIRES DE LA FRANCE’ (only the one of them is Gabriel’s, the other was added by Louis-Philippe; but the intention is clear enough), stand out against the Cour de Marbre, the centre of the entrance front, which can only be called fussy and domestic. Perversely, you get very fond of the applique stonework and the allegorical ladies and gents perching on the balustrade – but the chummy effect is entirely different both to what was intended and to the way in which Versailles is presented today. The garden front poses the same problem: the immense three-storey length, stone faced, is split into three parts, all but identical: Mansart could only think of treating the middle storey with some decorous architectural framing here and there. The result is hopelessly weak and stands no chance against the huge scale of the landscape, yet you become fond of little bits. To try and see everything is fatal: it can only lead to a total disenchantment which Versailles certainly asks for but does not deserve. Only a few things are as it were obligatory: the Grandes Appartements, the Opera, a few selected parts of the grounds. These are described separately. Otherwise it is a background for a vast human comedy of visitors and attitudes.

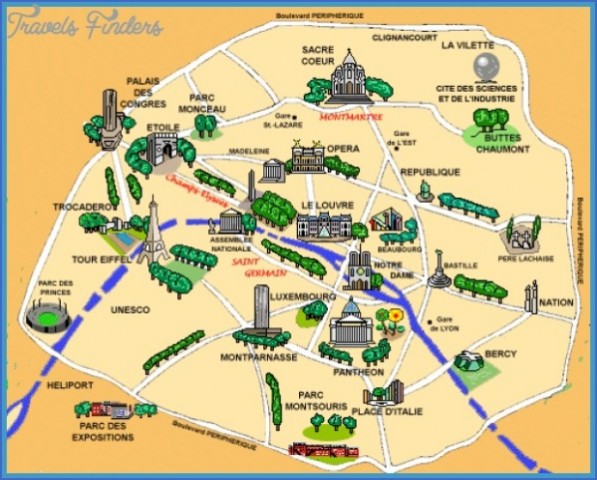

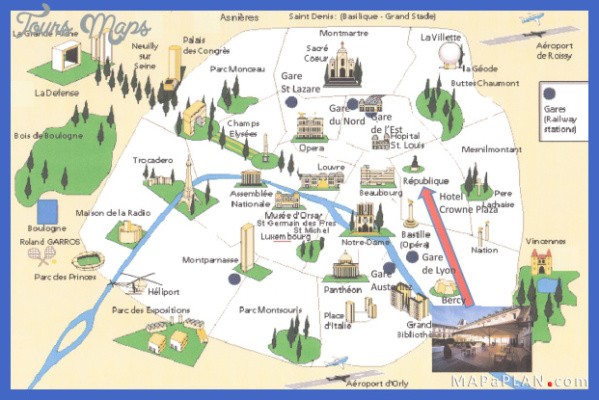

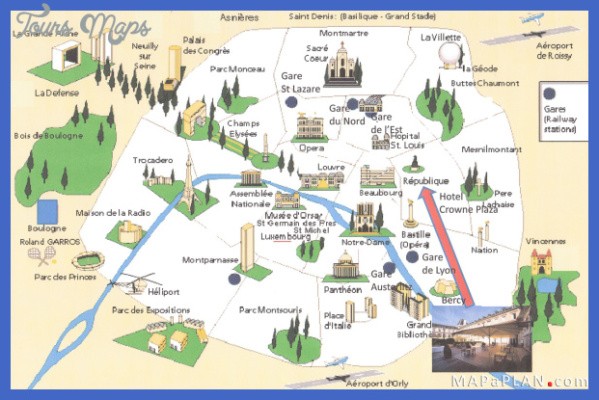

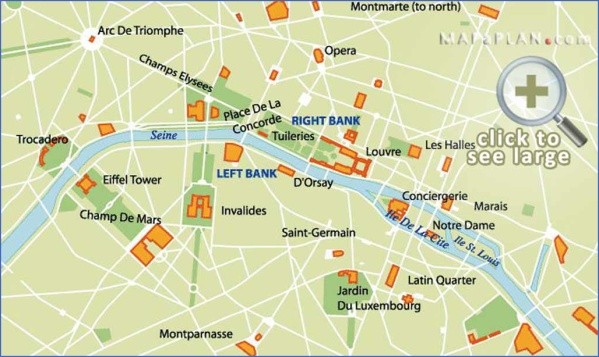

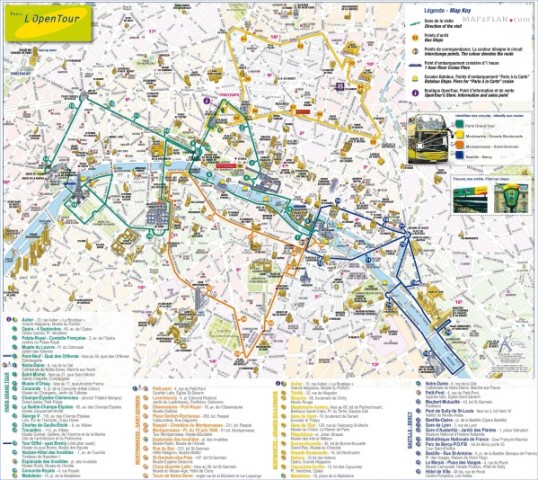

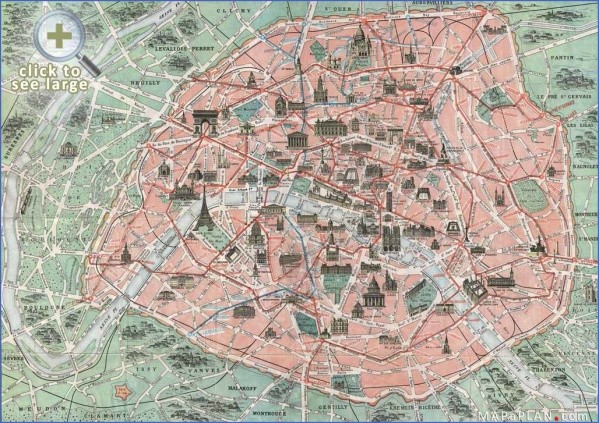

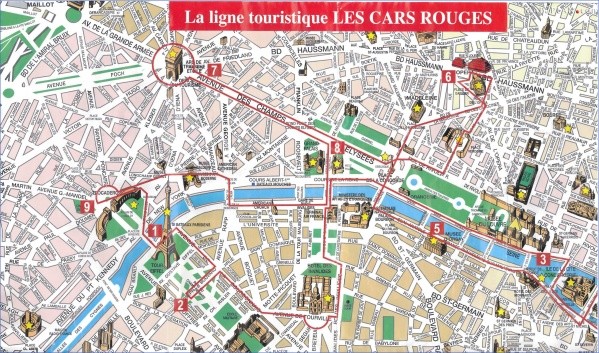

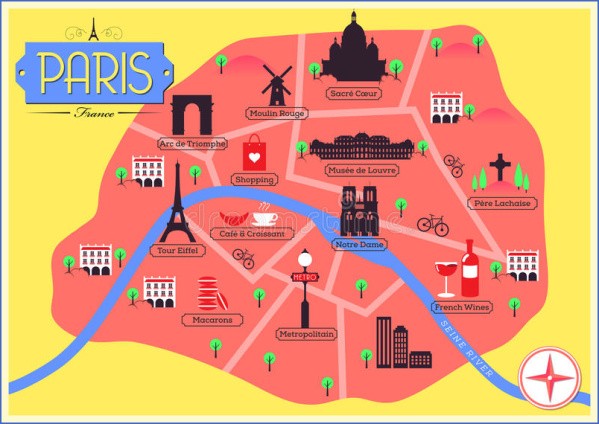

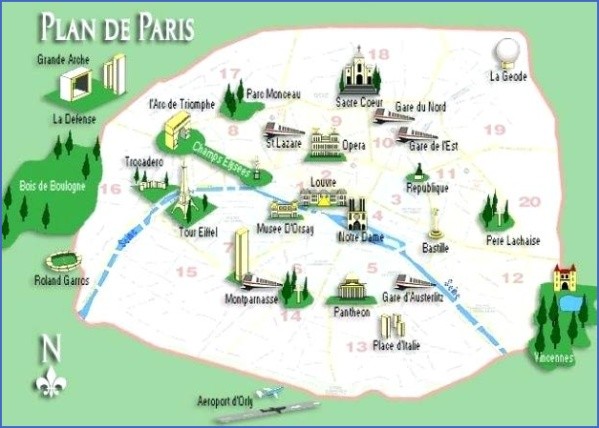

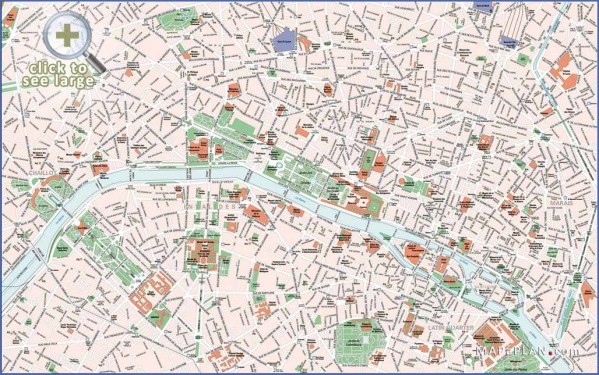

Paris Map Landmarks Paris Landmarks Map Photo Gallery

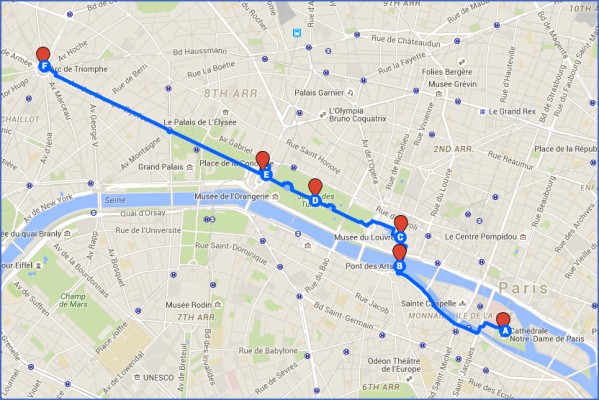

Paris Map With Landmarks Versailles: chateau, Grandes Appartements

This is as it were Basic Versailles, which is open all day and which you can visit without a guide though your ears may be assailed willy-nilly by the guides of other parties. The rooms were all designed by Mansart or Le Vau, except for a pleasant surprise at the end: they are the epitome of the official Louis Quatorze policy, and they go as far as impersonal and unimaginative grandeur can. Above everything else, they need to be used: most of all the chilly magnificence of the chapel needs organ music and a buzz of inattentive courtiers. The sequence of public rooms is pointless without at least the furniture, which was dispersed at the Revolution. Once you know that an otherwise indistinguishable gilded room called the Salon de Diane in fact contained a billiard-table, the thing begins to be comprehensible and sympathetic.

This is not true of the Hall of Mirrors – though even then, Orpen’s wonderful paintings of it inhabited at the Peace Conference of 1919 may seem more vivid than the real thing. It is one staggering coup d’&il like the view up to the Arc de Triomphe, running almost the whole length of the central block, an eighth of a mile. Lustrous gold and purple marble all reflected in the dulled mirrors – it cannot help but be breech-born into magnificence. But not a specific magnificence; nothing that could not have been created by any age granted these dimensions, that marble and those mirrors. The impersonality works itself out in further rooms until the Salle des Gardes, and then is rescued not by the architecture but the painting. David, with two large canvases of Napoleon crowning Marie-Louise (1808-22) and greeting his troops (1810) has achieved what all the earlier Lebruns and Lemoynes failed to do: a personal response to kingship. And beyond is the best part of the Grandes Appartements, the majestic Galerie des Batailles, built in 1836, under: the apparently unlikely auspices of Louis-Philippe – was it done by Percier and Fontaine? The subjects comprise every battle won by the French from the Dark Ages onwards: the result, huge and lucid, speaks of the Republic: the idea of a supreme ruler at last made bearable. And once out of the Appartements there is no better place to see that idea than the town of Versailles.

Versailles: chateau, l’Opera

Here, at last, is what it is all about. The artificiality is taken out of any uneasy contact with real life and conceived simply and frankly as a huge illusion. Gabriel was commissioned to build the theatre in 1753, took twenty years thinking about it and then finished it in a rush to be ready for the marriage of the future Louis XVI with Marie Antoinette in 1770. The result has the richness of Louis Quatorze and Quinize, the scale of Louis Seize: the effect belongs to the nineteenth century, not the eighteenth. Oppressiveness has gone, a grand overall sumptuousness replaces the detailed points of elegance. For an English visitor it is a great big Victorian romp with an extra edge of elegance.

(You are shown round in parties, about three times a day. The result is really worth waiting for; with luck the guide herself will provide a histrionic performance worthy of the setting, declamatory, powerful and emotionally exact.)

Maybe You Like Them Too

- Top 10 Islands You Can Buy

- Top 10 Underrated Asian Cities 2023

- Top 10 Reasons Upsizing Will Be a Huge Travel Trend

- Top 10 Scuba Diving Destinations

- World’s 10 Best Places To Visit