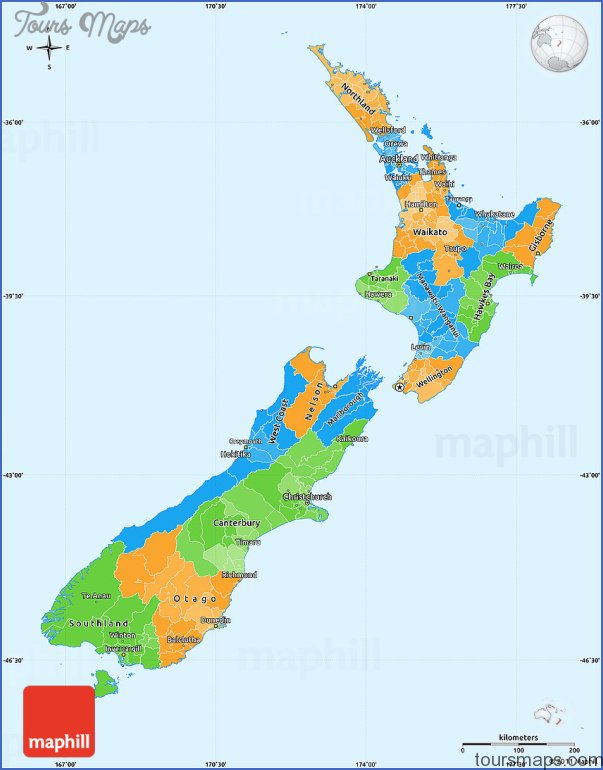

New Zealand Political Map

Nick Mills, who took over the viticulture and winemaking at Rippon from 2002 (his father died in 2000), attributes his own commitment to the vine and wine to Rudi Bauer. Between 1989 and 1992, when Nick was in his late teens and Rudi was working at Rippon, they spent time together – pruning, planting and talking. ‘Rudi sort of instilled in me the feeling that viticulture and winegrowing was something that I could potentially fall in love with,’ says Nick. ‘I got inspired at that time.’ But Nick had another talent to explore. He was a freestyle skier in the New Zealand team preparing for the Nagoya Winter Olympics when at the end of 1997 he hit a control gate in a high-speed turn and ‘lost my leg out behind me and blew it completely to bits. So that dream was out the window!’ His next four years were spent at the Beaune Polytechnic studying viticulture and oenology and working in the vineyards of Burgundy.

During the 1980s and 1990s, winegrowers in Burgundy became more and more concerned with reducing, or eliminating, many of the chemicals that had crept into their vineyard management. Centuries of growing vines on the same sites, and the increasing reliance on herbicides in the twentieth century, had resulted in the accumulation of undesirable chemicals in these vineyard soils. Tertiary institutions were embracing organic and biodynamic practices in the vineyard and cellar, teaching them and integrating Burgundy’s vine and wine history into their courses – notably the strong manual work ethic and respect for the vine held by the Cistercian order. Nick Mills was exposed to these ideas both in his studies and on the enterprises where he worked during his stages, or periods of practical experience. This experience deepened his commitment to organic and biodynamic practices and also to the people who were exploring and introducing them.

New Zealand Political Map Photo Gallery

At enterprises like Domaine Jean-Jacques Confuron in the commune of Premeaux-Prissey in the Cote d’Or, where organic and biodynamic practices were embraced, Nick Mills began accumulating a sophisticated knowledge of the biology of the vineyard and cellar. During his four years on the Cote from 1999 through 2002, Nick did stages at a number of diverse enterprises. With the 1999 Confuron experience under his belt, in 2000 he grasped the opportunity to work with Nicola Potel who is from a Volnay family but at the time was setting up a negociant business in Nuits-Saint-Georges. Here was a unique opportunity to experience the different nuances of the aromas, texture and flavours of Pinot Noir grown in the different communes of Burgundy by participating in their vinification. For the 2001 vintage, he arranged a job with Pascal Marchand at the Domaine de la Bougere, pruning and working in the cellar until the spring of 2002. Lastly, he worked in the prestigious Domaine de la Romanee Conti vineyard and cellar from April 2002 before heading home. Experience garnered at all these enterprises prepared Nick for his return to Rippon Vineyard.

He came back to a 15-hectare vineyard with 12 hectares of vines in production, about nine of them in Pinot Noir. By Burgundian standards the vineyard was a suitable size for a family holding. His experience in France had made him certain of one thing: ‘I was already convinced about biodynamics.’ His was a practical rather than an ideological attraction to the approach. Minimal intervention in the growing of the grapes and in converting them to quality wine is his philosophy and Central Otago is the ideal place to practise it. Its dry atmosphere reduces the incidence of many diseases that are a problem in other grape-growing regions of New Zealand. Consequently, Nick did not even consider using herbicides to control unwanted plants. He disced the whole vineyard and ‘created the mound underneath the vines so I could work the under-vine cultivator properly’.

From the beginning, Rippon Vineyard was organic. Achieving this certification required them to vinify grapes from their own vineyard only. When Rolfe and Lois began planting vines at Rippon no vineyards existed within tens of kilometres of them. They limited their applications of sprays until their practices were certainly organic, and verging on the biodynamic. As the operation became more commercial and Rolfe became less involved in the day-to-day and seasonal management of the vineyard Rippon drifted from its earlier ideals of limited intervention in the life of the vines. By the late 1990s, when nearby Wanaka growers pressed them to buy small quantities of Pinot Noir, they obliged and their organic status was compromised.

Nick Mills’ biodynamic beliefs in the benefits of manual labour and observation in growing grapes of quality have had consequences for everyone who is working at Rippon in the twenty-first century. Practices embedded in the Burgundian tradition are incorporated into daily organic and biodynamic routines. Parcels of mature Pinot Noir vines have been named after ancestors – Emma’s Block for the great-great-great-grandmother of the current generation of the Mills family and Tinker’s Field for the late Rolfe.

Twenty years earlier Nick had bought a hand hoe for Rolfe in Switzerland. They had fitted it with a kanuka handle. Hand cultivation of the vineyard had been part of their regime when Nick was growing up: ‘We were buying hand hoes from Mitre 10 and we went through dozens and dozens of them.’ But the rugged Swiss hoe had outlasted all others. So Nick used it as a template and had 20 more of them made up:

And we do an hour hand-hoeing every morning, across the board, everyone on the property. We arrive in the mornings, we shake everyone’s hands, we look each other in the eye and we go out and do an hour’s hard yakka every morning. It really galvanises a team.

We’re in this together. That’s the shop people, that’s the winery people, that’s the office people, it’s everyone.

Rolfe Mills would undoubtedly have admired the depth of Nick’s tribute to this lineage and this place.

Maybe You Like Them Too

- Top 10 Islands You Can Buy

- Top 10 Underrated Asian Cities 2023

- Top 10 Reasons Upsizing Will Be a Huge Travel Trend

- Top 10 Scuba Diving Destinations

- World’s 10 Best Places To Visit